It has long been known that birds, and even humans, use celestial cues to navigate vast distances.

Now, tiny nocturnal Australian insects have been found to use stars as a guiding compass during their long annual migration.

Interestingly, the Bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) is the first invertebrate ever observed using a stellar compass for long-distance navigation.

“Bogong moths are incredibly precise. They use the stars as a compass to guide them over vast distances, adjusting their bearing based on the season and time of night,” said Eric Warrant, Professor of Zoology at Lund University.

To unravel this migration mystery, the study also involved researchers from the Australian National University (ANU), the University of South Australia (UniSA), and other institutions worldwide.

Decoding the navigation mystery

When spring arrives, large moth swarms fly up to 1000 kilometers (roughly 621 miles) from their breeding grounds across southeast Australia.

They head for a few cool, dark caves and rocky outcrops tucked away in the Australian Alps.

There, these one-inch-long insects spend the entire summer hibernating in cool, alpine caves to escape the heat. When autumn arrives, the moths make the arduous return trip, completing their life cycle by breeding before they eventually die.

This was long considered one of nature’s most baffling migration mysteries, but not anymore.

Earlier, experts had already discovered that these moths can sense the Earth’s magnetic field. Now, researchers believe they’ve finally unraveled the full navigational mystery.

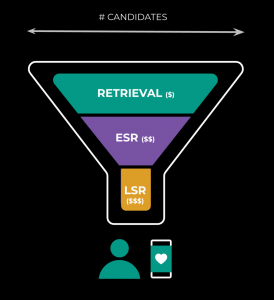

Turns out, these nocturnal moths combine stellar cues with Earth’s magnetic field to precisely locate a never-before-visited destination.

The team put the moths to the test using flight simulators.

For the experiment, they reportedly constructed a black-felt-lined arena, resembling a miniature planetarium, in the Snowy Mountains.

Bogong moths were caught during their migration and carefully secured in the middle of this set-up. Though tethered, the moths continued to “fly like mad,” allowing scientists to observe their maneuvers and changes in direction.

Brain activity recording

Under a starry sky, the moths consistently flew in the correct migratory direction: south in spring and north in autumn.

The moths adapted their flight when the stars were rotated, but scrambling the stars made them lose all sense of orientation.

Even more remarkably, if clouds obscured the stars, these clever insects switched to a backup system: Earth’s magnetic field.

This dual compass ensures they can always find their way to right location, come rain or shine.

“This proves they are not just flying towards the brightest light or following a simple visual cue. They’re reading specific patterns in the night sky to determine a geographic direction, just like migratory birds do,” said Prof Warrant.

A separate experiment involved implanting an electrode into the moth’s brain to measure brain activity.

The team pinpointed specialized neurons in the moth’s brain that react to the orientation of the star-filled sky. Most notably, these cells—situated in brain areas controlling navigation and steering—show the strongest activity when the moth is oriented southward.

Researchers note that this kind of directional tuning shows the moth brain encodes celestial information in a “surprisingly sophisticated way.”

The precise features in the night sky that guide these moths are unknown. Possibilities include the Milky Way’s distinct band of light, a vibrant nebula, or other yet-to-be-identified elements.

As per the press release, this discovery could even inspire new technologies in robotics and drone navigation, and crucially, inform conservation efforts.

The findings were published in the journal Nature.